Understand Peak

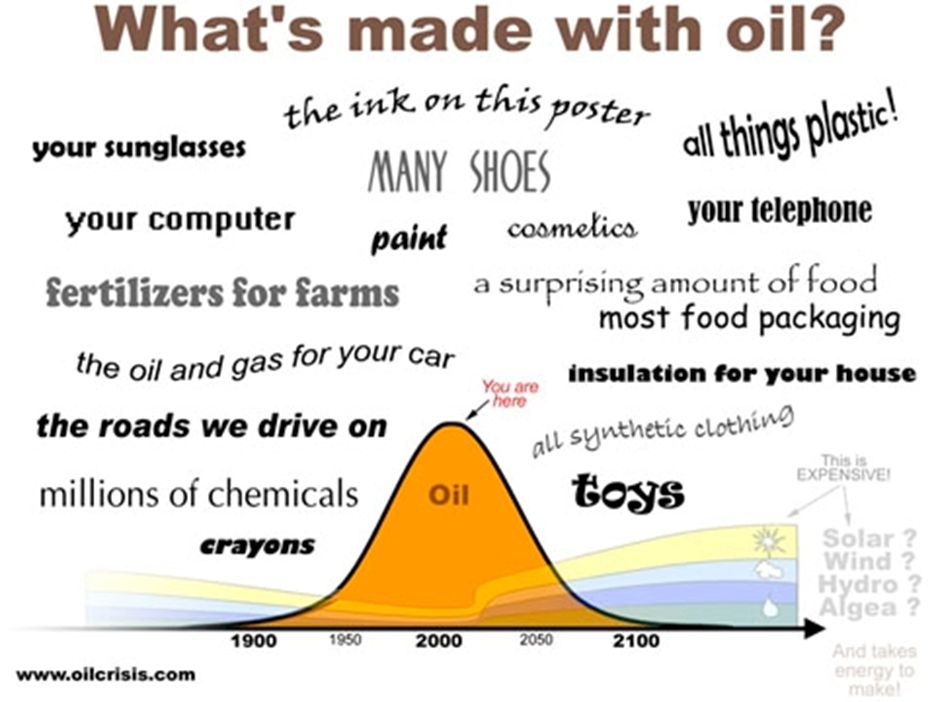

Peak oil is the concept that oil is a limited and finite resource, that when its production history is modeled, it will follow a certain profile. This concept of peak can be useful when we talk about any limited resource.

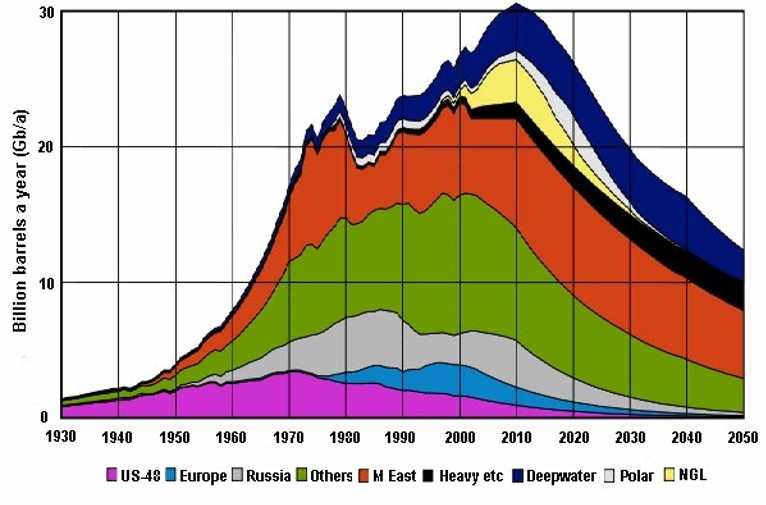

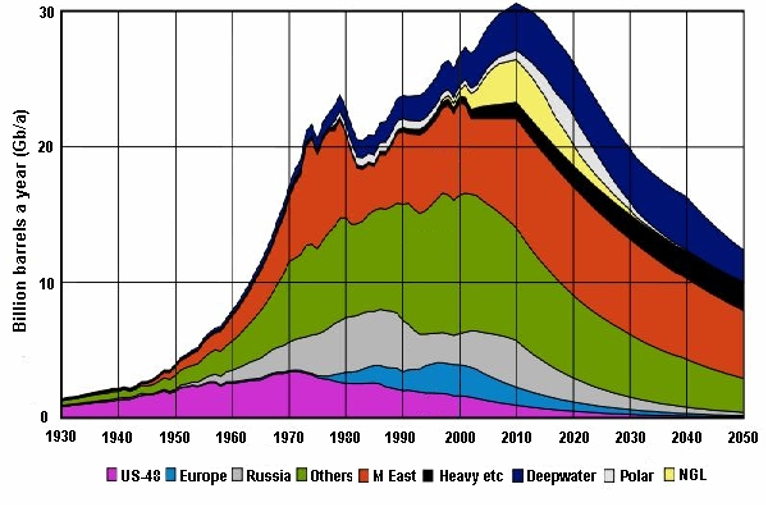

In 1956 geologist Marion King Hubbert noticed that the production profile of single oil wells followed a bell-shaped curve. He attempted to apply this model to the oil industry as a whole. He developed what is now known as the Hubbert curve. This curve illustrates not just the early days’ increasing supply, but it has a clear peak. And — what’s more important to our discussion today — it illustrates the aftermath of peak.

Hubbert’s work reminds us that oil is a finite resource. Sure, the earth makes more of it, but it makes more very, very, very slowly — particularly when compared to how quickly humanity is using it. So for purposes of human timescales, we must consider oil to be a finite resource. And right now, we are likely delving into the declining second half of planetary oil supplies.

Hubbert’s work influenced many environmental thinkers including David Holmgren (co-founder of the Permaculture movement), Richard Heinberg (author of Peak Everything and co-founder of The Post-Carbon Institute), and Rob Hopkins and Naresh Giangrande (founders of the international Transition Towns movement).

In recent years, discussion of peak oil has waned, in part because fracking practices kicked the can down the road a bit, allowing us to ignore peak for a few more years. But discussion of peak oil also eased because James Hanson’s announcements about greenhouse gas accumulations have made climate change a far more urgent issue.

In this series we’re going to look at the concept of peak in terms of what it can teach us about any finite resource.

The psychology of Peak

People who’ve studied peak theory point out that there’s a certain psychology to peak as well.

As humanity experiences the tremendous increase of supply in the early years — of an oil well, or any extracted asset — there’s a perception that everything is fantastic, and supply is unlimited. We invent more and more ways to use this wonderful resource. There’s a feeling that this will never end.

When supply reaches peak, and then begins to ease off, physical reality kicks in. We move into the declining second half of the planetary supply.

The easy-to-get-to stuff has already been used up. All that’s left is the hard-to-get-to stuff — for example deep water oil, Arctic oil, layered deposits that require fracking — all of which are far more expensive, and highly destructive, to extract.

People who’ve studied peak theory say that at peak, we see wild price fluctuations and competition over what’s left. The abundant supply which once was possible now becomes more constrained. And meanwhile, we have a whole society that’s built around the precious substance. We’ve built businesses, entire industries, economic structures, all constructed upon the presumption that it will forever be cheap, plentiful, and unlimited.

Peak and secondary products

For just about any substance in today’s marketplace, there are primary uses, and then there are secondary uses that were developed to use byproduct, the parts that would otherwise have been wasted.

In the case of oil, we tend to think of oil for its primary uses such as gasoline, airline fuel, etc. However the byproduct of making those pure products out of crude oil gave rise to things like asphalt, a wide assortment of plastics, and many other products that we use every day.

As we navigate the declining second half of the planetary oil supply, we need to remember that all these secondary applications will similarly suffer the effects of post-peak.

Pinpointing “peak”

One thing about a Hubbert curve is, you’re only able to accurately identify true peak in retrospect, after it has already occurred. Combine that with the fact that oil companies are very secretive about the actual supply they control, and there is political power at stake too. So people debate: Did we hit peak oil in 2008, 2010, or will it be 2026? Or is the whole concept of “peak” useless?

But focusing on “exactly when is peak” misses the point

The point is: this resource is not unlimited. It never was. We all made a mistake to think of it like that. At some point the party ends, things get tougher, and things that once were so easy become less possible.

Post-peak

Post-peak realities mean the supply chain for the key substance and all its derivatives gets disrupted. While we aren’t going to run out, we aren’t going to have zero oil tomorrow, the cost of getting oil — certainly at the volume we have become accustomed to — is getting prohibitive.

While the post-peak era can mean uncertainties in physical product and supply chains, we’re most likely to feel it economically first. Price competition over that declining second half will mean upheaval in economics models and cost expectations, and it could potentially mean upheaval in governments and international relations.

No matter how you look at it, once we cross into the declining second half, it means disruption.

Why haven’t we heard more about this? In an analysis paper, “Peak oil, 20 years later: Failed prediction or useful insight?”, Ugo Bardi writes:

… peak oil predictions were considered incompatible with the commonly held views that see economic growth as always necessary and desirable and depletion/pollution as marginal phenomena that can be overcome by means of technological progress. That was the reason why the peak oil idea was abandoned, victim of a “clash of absolutes” with the mainstream view of the economic system. In the clash, peak oil turned out to be the loser, not because it was “wrong” but mainly because it was a minority opinion. (Bardi 2019)

A bit of historical perspective

It’s important to view peak oil in perspective. When we look at peak oil within the scale of written history, we realize that cheap, plentiful oil has only been available to humanity for a very brief time period.

All of us who are alive today (including my 96 year old father) have only known life within the oil age. That means we slide into thinking “this is the way things have always been, the way things will always be.”

We need to remember people lived happy, healthy, productive, connected lives before the brief era of oil, and people will live happy, healthy, productive, connected lives after the time of oil.

It’s up to us to design it that way.

The future with less oil could be better than the present, but only if we engage in designing this Transition with creativity and imagination.

— Rob Hopkins, co-founder of the Transition Towns movement

Which way forward?

The concept of peak oil reminds us that oil is not an unlimited resource, and the abundance-party’s pretty much over. At some point fairly soon, humanity is going to have to quit depending on oil. We can’t keep going as an oil-dependent society. Peak oil says: Like it or not, we’re going to have to move away from oil.

And climate change says: We’ve got to make that move ASAP.

What’s more, oil is not the only substance for which humanity has reached peak. Richard Heinberg popularized the term peak everything. It goes by other names, such as biocapacity.

Reflection – Understanding Peak

What does it mean to have “limits”? When in your life can you remember having limits? Perhaps it was a parent telling you not to run into the street, the edge of the sidewalk was your limit. Perhaps it was a limit to how much cake you could eat. In particular, think about limits that had some sort of physical or biological component to them.

- How do you feel about limits?

- What are your observations about current American societal views about limits?

- What are your observations about limits that Nature imposes?

This post is part of the What We Can Do series — see the full project.

What is Sustainability?